…

- 241 Posts

- 410 Comments

1·7 days ago

1·7 days agoUhuhuh. What a wuss.

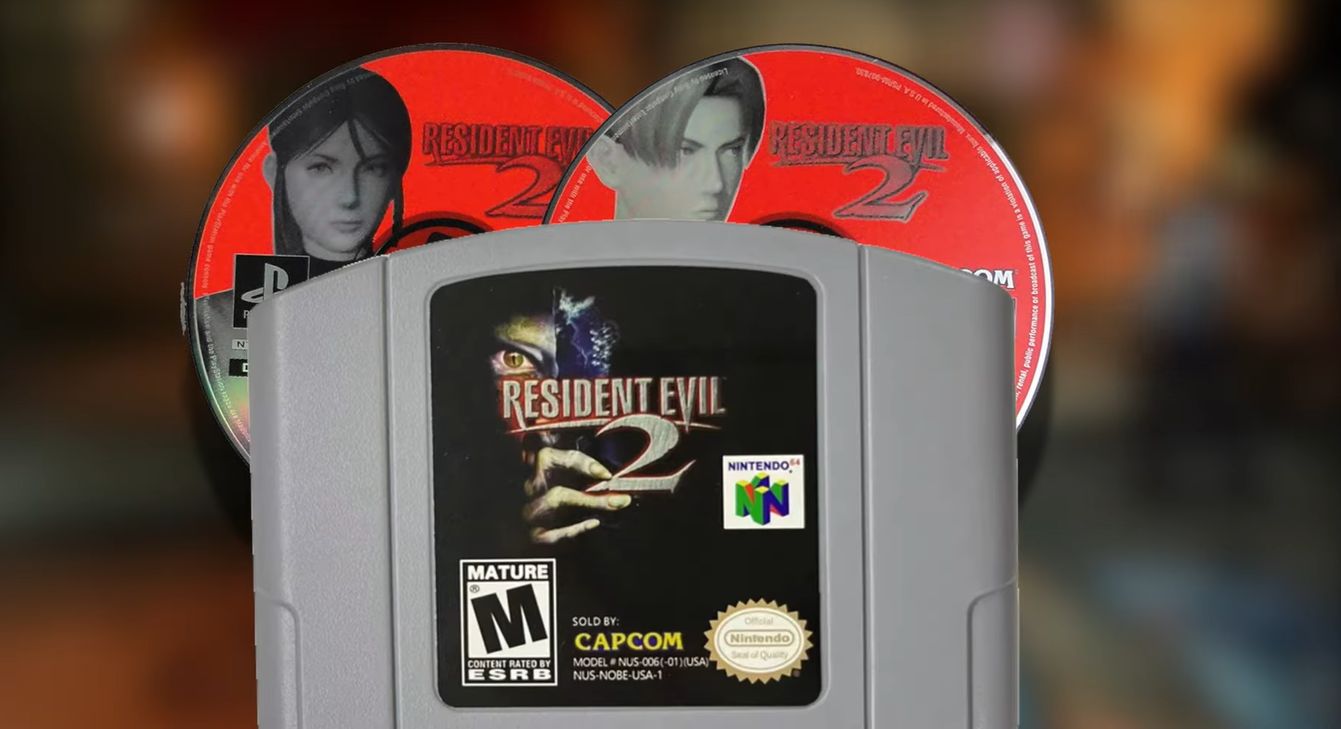

I’m pretty sure this is actually my exact crop of the meme (I cropped out an ugly ifunny logo).

https://lemmy.world/post/41780741

But you know, I stole it from somewhere else anyways.

Checkmate.

451·21 days ago

451·21 days agoIt’s not a “Christian game”, its a game where the setting is a violent, fractured place and Christianity has a large in-universe footprint, influencing factions.

Iron Tower Studio games makes quite good RPGs.

11·23 days ago

11·23 days agoHow would you, in general terms, construct an arrangement between a publisher that is funding development, and a developer? How would the agreement hold a developer to certain standards without any kind of time or budget limitations?

1·23 days ago

1·23 days agoI’m not trying to be cute. If a publishing company gives money to a developer who is a separate entity to make a game, they’ve got to have some kind of contract. If there is no timeline or total budget written into the initial contract, how could a publisher pull out of that agreement?

If the answer is going to be “publishers can just pull out when they feel like it” then that’s neither adhering to the “let devs develop ‘until it is done’.” philosophy that is the entire point of this hypothetical restructure, and it for practical terms it does impose a deadline based on the publisher’s patience, except now that deadline is not expressly clear and simply defined.

If publishers can’t simply pull out on a whim, then without some kind of limiting factor that denotes a failure to perform where by a specific time a publisher can point to that failure, it can’t really be functional contract. Saying “the game must have x, y, z features” but never putting a time or budget limit in place means the developers can never have failed at implementing the features because they just haven’t gotten around to it yet.

1·24 days ago

1·24 days agoIn a publisher fronting money to developer situation, without a fixed time limit (or money limit, which functionally translates to a time limit) is the publisher just infinitely on the hook to pay for dev time “until it’s done”?

31·24 days ago

31·24 days agoLet’s look at the initial comment in the chain:

all game developers need to put their foot down and say “it’s ready when it’s ready.”

No marketing deadlines, no “crunch time,” make the game until the game is made

It isn’t saying publishers should be more flexible about deadline delays, it is saying there simply shouldn’t be deadlines at all.

Shoveling infinite money at a developer who tells you it will be ready when it’s ready is the Chris Roberts model of game development. While it certainly produces interesting results, it is unrealistic and undesirable to expect it as the standard.

Games that are developing well but need a little more time to fix issues should be given flexibility by publishers, but at the end of the day there are stretch ideas and content that has to be cut. Doing that cutting and keeping the project focused is what a lead on the dev team should be doing throughout the entire development. If a game has a realistic deadline given the expected scope and the dev team comes back and says they actually need another year of production, then it is worth looking into if that extra time is going to make the game a year’s worth of investment better or not.

5·24 days ago

5·24 days agoPublishers are considering return on investment. In a model where they are providing the game budget to the studio, every delay means more money out of their pocket. Case by case it might be worth it, but just allowing developers to infinitely say it’s “almost ready, just one more delay” isn’t reasonable.

I know from the hard core gamer audience that discusses this stuff online there is often this vibe that nothing should be cut from games. People look at various interesting cut content and lament it for not getting enough time, but there is always going to be cut content.

If there isn’t a lead on the development team putting their foot down to control the scope and focus the team, and a similar push for focus by a publisher you get a meandering unfocused project that goes over budget.

In the solo/small amateur team dev, self-publishing model that ROI pressure isn’t coming externally from a separate publisher. It is means solo devs are making their first games usually on a budget of nothing, as a side project to their day jobs. In some cases like with Concerned Ape it turns out great. In many cases development comes out tediously slowly, like with Death Trash. In innumerable cases the games just die.

In cases like Wasteland 2 it was a full professional team working full time using crowdfunding. An alternate model, but still limited by budget pressure. There was no publisher to pay back, but when the crowd funding money was gone, it was gone. That game did come out and it was enjoyable, but clearly it wasn’t “done when it’s done” levels of polish by the team since they used the profits from the game to release a “Director’s Cut” which was a whole polishing pass on the game they simply couldn’t afford the first time.

41·24 days ago

41·24 days agoThe above comments were talking about how this policy should apply to every game development project. Which is a nice thought, but not realistic for every situation.

I pepsi what you’re saying.

If it isn’t an elaborate joke, then someday I want to talk with the creator at great length.

Solid gold, start to finish.

“Truly this is a First Contact.”

The Van Halen radiation belts rock too hard though.